I am genuinely looking forward to seeing Rick Wakeman in concert.

Yeah, yeah, I know; I have never been a fan of either Yes or prog in general. However, I interviewed the guy once back in the mid-70s, when he was touring one of those stupid spectacle-rock things that were all the rage then; I think it was something like King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table On Ice. And to my surprise he turned out to be utterly charming, unpretentious and basically the most hilariously funny celeb I ever killed an hour and a half with over drinks and lunch.

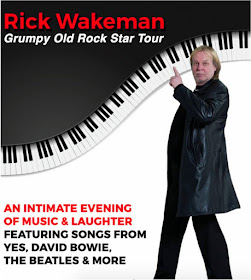

That being the case, I will be attending his new show when it comes to my old stomping grounds in Jersey in October; if you'd like more info on the tour, you can get it HERE.

POSTSCRIPT: When I interviewed Wakeman, he let it drop that during his early days as a session guy, he had played on the 1970 album by The Pipkins (although not on their hit single "Gimme Dat Ding").

That's right -- Wakeman is tickling the ivories on THIS immortal classic.

Obviously, it was a long strange trip between that and Tales From Topographic Oceans.

Loved Gimme Dat Ding, the ultimate ear worm. Never heard this one before.

ReplyDeleteAs Arte Johnson would say, very interesting.

ReplyDeleteIf you get a chance, go to YouTube and watch Wakeman's speech at the Rock Hall induction ceremony. This guy is freaking hilarious.

ReplyDeleteExactly Steve.

ReplyDeleteI had no idea that Wakeman was as funny as he was until I saw the RRHOF deal.

Everybody knows about the Wrecking Crew, but I wonder if anyone has ever done a book or film about the great British session cats (Wakeman, Blackmore, Cattini, Spedding, Page, Hopkins, et al).

ReplyDeleteAlzo: what a great idea. I'd love to see a film about the great Brit session guys. Meanwhile, from the book Bathed In Lightning...

ReplyDeleteArt takes time, yet the idea of pop music as art was wholly new, and far from accepted, in 1966. While the Beatles were in the vanguard of bringing popular music out of the ephemeral and into history, thanks to their innate talent and musical curiosity, and to the leverage on studio time and freedom in creativity that their unprecedented commercial success had bought them, others were moving in the same direction.

All of them were happy to use session musicians as and when required: the Beatles would use the likes of Ronnie Scott and the Night-Timers’ Eddie Thornton, for example, uncredited on their records. But then no one in the Beatles happened to be a sax player or a trumpet player, and no one outside of them assumed they were.

A rung or two down the ladder, but destined to be held in similar acclaim

as an artist who brought richness, depth and credibility to his medium, RayDavies of the Kinks had willingly conceded to using session drummer BobbyGraham on what became his group’s breakthrough releases.1 He would also rely heavily on the (only occasionally credited) session pianist Nicky Hopkins during the decade.

‘Session players are, for the most part, anonymous shadows behind the

stars,’ Ray reflected, many years later. ‘They do their job for a fee and then leave, rarely seeing their names on the records. Their playing never stands out, but if you take them out of the mix, the track doesn’t sound the same. You only miss them when they are not there.’

Ray’s observations were astute. He could very easily have been referring to the solid, unobtrusive work of players like John McLaughlin or John Paul Jones; only some, like Big Jim, Jimmy Page or Nicky Hopkins, would get the opportunities to add something of their own personalities to the records of others.

‘When I was working on recordings by [other people], I was working for

them,’ said bassist Herbie Flowers, who would work with John on a couple of David Bowie sessions, ‘so I had no comment about any of it; it’s like asking a bus driver what he thinks of the bus. “It’s a bus, innit, and the roads are a bit bumpy.”’

The funniest sensation,’ said Nicky Hopkins, ‘is working with someone

who’s currently a hot name, and then three months later he’s faded out and there you are, still banging away.’